“The practice of representing atrocious suffering as something to be deplored, and, if possible, stopped, enters the history of images with a specific subject: the sufferings endured by a civilian population at the hands of a victorious army on the rampage” (Sontag, 2003, p. 38).

Since the dawn of time mankind have found reasons to wage war with each other, and, through song, story and sketch, glorified and romanticised the notion of warfare and every great conflict along the way. This is evident throughout history in pieces such as The Alexander Mosaic (100BC), a Roman floor mosaic depicting the armies of Alexander the Great defeating Darius III, Theodore Gericault’s An Officer of the Imperial Horse Guards Charging (1812), and Carle Vernet’s 10th Regiment of Hussars (1812). I mean, what’s not to love? Honour, love and sacrifice, blood, sweat and tears, heroes fighting for God, country and freedom… They’re basically the cover art for every great action narrative. So really, its no wonder for thousands of years we kept passing down through art the same admiration and idealisation of war.

Left: Theodore Gericault (1812), Right: Carle Vernet (1812), Bottom: Roman floor mosaic (100BC).

This began to change around the mid-19th century as warfare started to evolve into a mechanised affair. The shift was led by artists and collections such as Francisco de Goya’s The Disasters of War (1810), Eugene Delacroix’s The Massacre at Chios (1824), and Elizabeth Thompson’s The remnants of an army, Jellalabad, January 13, 1842 (1879). However, sentiment towards conflict still varied drastically from country to country depending on the degree of their recent exposure.

Left: Eugene Delacroix (1824), Top Right: Elizabeth Thompson (1879), Bottom Right: Francisco de Goya (1810).

And then there was the Holocaust.

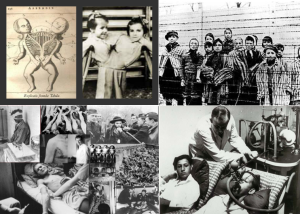

Over 6 million Jewish people, which represented around 70% of Europe’s Jewish population, and included 1 million children, were systematically annihilated between 1941 and 1945 by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany regime in what was one of the deadliest and most organised genocides in human history (Niewyk & Nicosia, 2000, p. 45). A combined network of around 42,500 facilities and 200,000 perpetrators throughout Germany and its occupied territories were used to concentrate the victims for various purposes, including slave labour, mass murder, medical experimentation, and various other heinous abuses of man’s most fundamental human rights (Lichtblau, 2013). It was conducted in several stages, beginning with state sanctioned social exclusion and culminating in what was intended to be the complete extermination of Jewish culture in Europe, an outcome the Nazis termed, “The Final Solution to the Jewish Question” (Niewyk & Nicosia, 2000, p. 46).

If every armed conflict from the Mesopotamian war of 2700BC to World War I wasn’t enough to persuade military art to reconsider its destructive position on this subject, the unprecedented catastrophe that was the Holocaust grabbed it by the throat, held it to the ground and forced it to. Never again could we allow this to happen. Never again could we install into the next generations’ minds a naïve, distorted thirst to rush into the front line. And never again could we allow such needless, rampant death.

And that is why artistic representations of war, painted, photographed and otherwise, are so important in contemporary society. In the words of Scottish war photographer Alexander Gardner, “pictures… convey ‘a useful moral’ by showing ‘the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry… Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity” (Gardner, 1863, cited in Sontag, 2003, p. 47).

Obviously it’s not a perfect solution. Plenty of powerful war photographs have been staged or doctored, and plenty of wars and conflicts have ravaged this world since 1945 whilst anti-war art was exhibited left, right and centre. But this does not mean that artwork has not had an impact.

A tapestry copy of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), arguably the most famous contemporary anti-war artwork, has been displayed within the United Nations building in New York City since 1985, serving as an ever-present reminder of the brutal consequences of war to those who function to preserve global peace (Conrad, 2004), Nick Ut’s photograph of Phan Thi Kim Phuc (1972) accelerated a wave of anti-war sentiment ultimately resulting in the US withdrawing from Vietnam a year later (Asselin, 2002, pp. 155-156), and the photos and videos taken during the Allies’ storming of Germany’s concentration and death camps in 1945 was critical in sentencing the inner party members of the Nazi Party during the Nuremberg military trials, as well as showing the whole world what really happened behind the closed doors of Nazi Germany (Roland, 2012).

Left: Nick Ut (1972), Right: German death camp (1945), Bottom: Pablo Picasso (1937).

But the ramifications need not be this extreme. All it takes is a single piece stirring within a person a sense of horror, shock or disgust about the devastation of war, and the ripple effect just within that one person’s life may extend outward, having a potentially infinite effect. And that honest power is why military art is so important within our society.

References

Asselin, P 2002, A Bitter Peace: Washington, Hanoi, and the Making of the Paris Agreement, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, pp. 155-156.

Conrad, P 2004, ‘A scream we can’t ignore’, The Guardian, 10 March, viewed 20 March 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2004/oct/03/art.

Lichtblau, E 2013, ‘The Holocaust Just Got More Shocking’, The New York Times, 1 March, viewed 19 March 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/03/sunday-review/the-holocaust-just-got-more-shocking.html?_r=0.

Niewyk, D & Nicosia, F 2000, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust, Columbia University Press, New York, pp. 45-46.

Roland, P 2012, The Nuremberg Trials, Arcturus Publishing Limited, London.

Sontag, S 2003, Regarding the Pain of Others, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, pp. 36-47.